The debt ceiling crisis has been averted, and this should be cause for unalloyed celebration. The bipartisan agreement was reached just a few days before the June 5, 2023, deadline that US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen stated as when the government would likely be unable to meet all its obligations.

The debt ceiling agreement removes an important uncertainty from the horizon, which is positive for financial markets, for the economy and for the US international standing. And it does so without imposing a major fiscal tightening, which might have caused growth concerns. All this is certainly good news.

The long-term risks linked to the fiscal outlook, however, have in my view become bigger, and market participants would do well to keep this in mind. Let me explain:

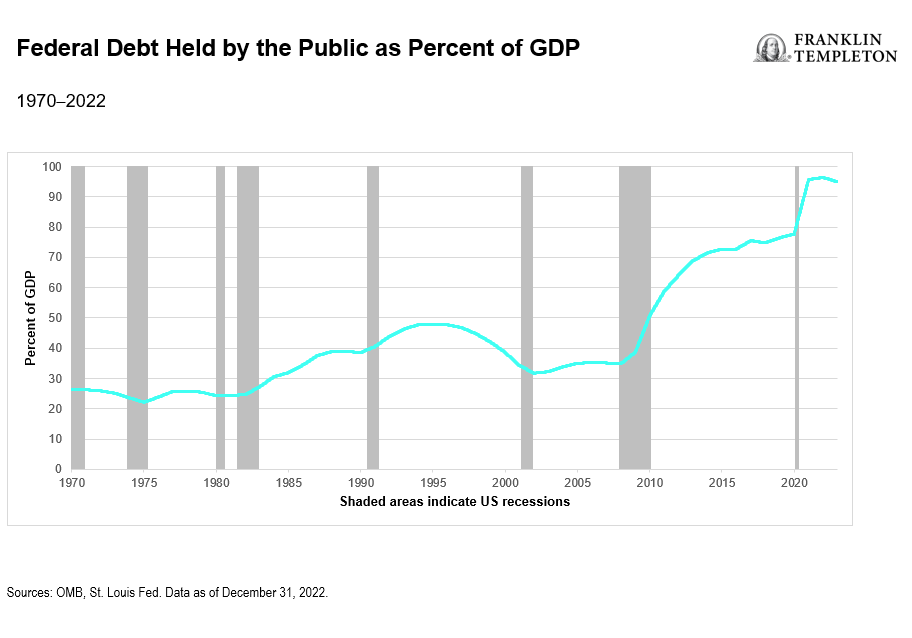

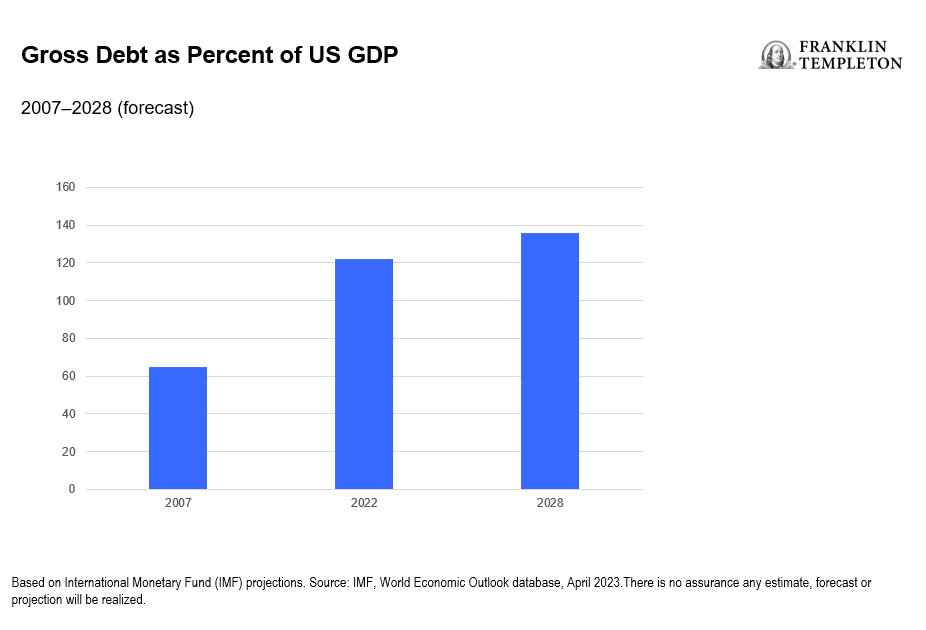

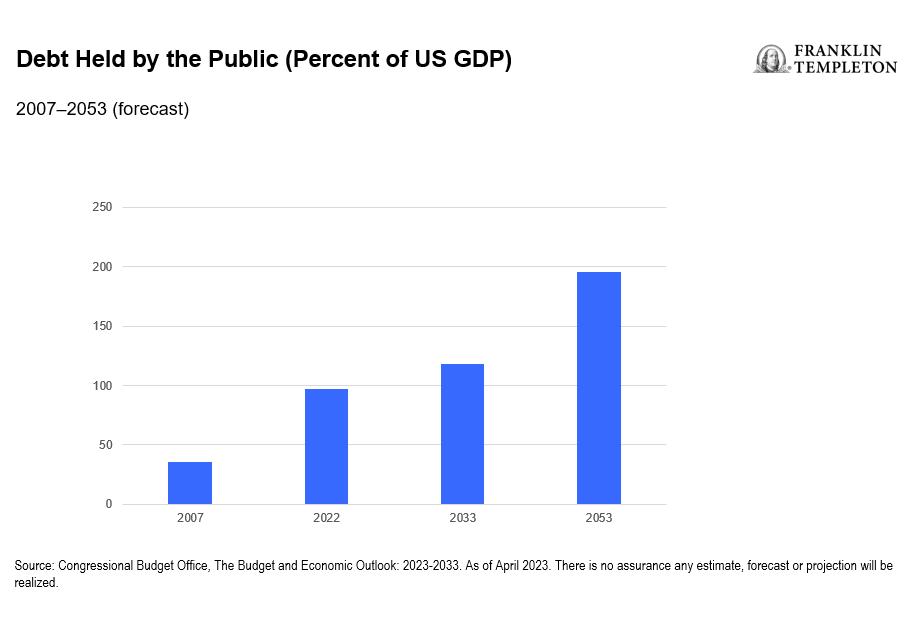

- The long-term fiscal picture is not getting any better. Based on International Monetary Fund (IMF) data, at the end of last year, US general government debt stood at over 120% of gross domestic product (GDP), twice the pre-global financial crisis (GFC) level (2007) and higher than most European union (EU) countries. The IMF projects it will approach 140% of GDP by 2028. If we look at debt held by the public,1 the measure more often used in US domestic discussions, the numbers are a bit lower, but the trend looks equally worrying. It stood at 35% of GDP before the GFC, reached 97% of GDP last year, and looking forward, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects it to reach 120% of GDP by 2033 and close to 200% of GDP by 2053.2 (Caveat: the latest CBO budget outlook was released last February and predates the debt ceiling agreement.)

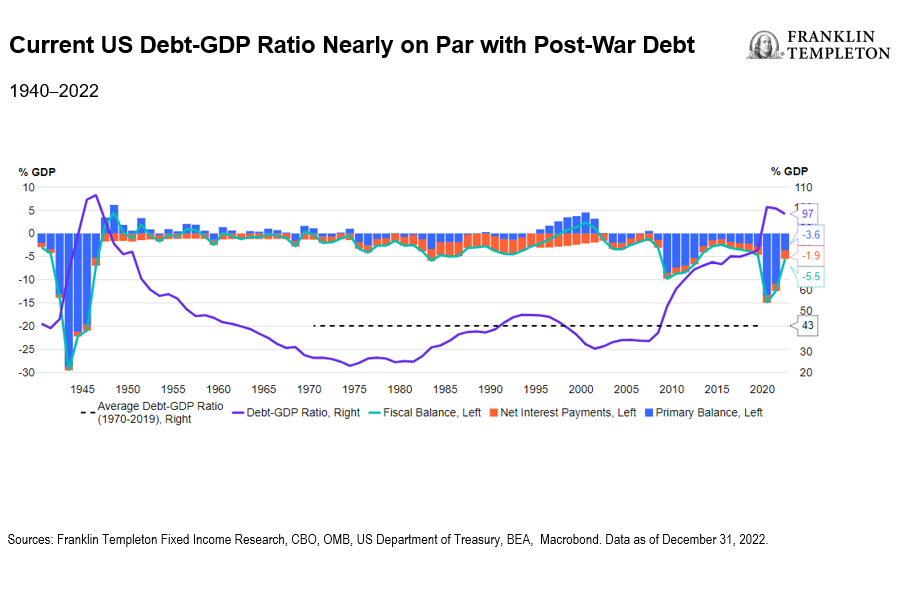

To put things in even starker historical perspective, the debt-to-GDP ratio has almost reached post-World War II levels:

- The recent contentious discussions on possible spending cuts have highlighted the underlying problem: discretionary spending accounts for just over one quarter of federal outlays, or 6.6% of GDP (as of 2022); non-defense discretionary spending is a paltry 3.6% of GDP—not much room for fiscal adjustment there. The other three quarters of public outlays consist in mandatory spending (16.3% of GDP), mostly entitlement programs such as social security and health care, and much harder to reduce, especially against the background of an aging population. To make matters worse, the days when the government could borrow almost for free are most likely gone, so interest costs on the debt will weigh a lot more on the budget. Net interest payments are projected to rise sharply from the average of the post-GFC period, to account for about half of future fiscal deficits.

- Political polarization has increased significantly over the past several years, and as of now there is no sign of it going into reverse. This will make it even harder to reach agreement on any durable adjustment to government revenues or expenditures—something that would be a delicate and demanding task even in a more collaborative political climate.

- This would make for a challenging fiscal outlook in any country. In the United States there is the added institutional complication of a debt ceiling that is fixed in nominal dollar terms. As the economy grows, even just keeping debt stable as a share of GDP therefore requires active decisions to raise the debt limit. As a consequence, high-stakes discussions on the debt ceiling are an intrinsic part of the process. In calmer times, the revision of the debt ceiling should just be the natural outcome of level-headed discussions in the budget process. That, however, is not always the case, as we have seen.

- Financial markets seem to be getting used to the default threat. Over the past several weeks, investors remained relatively calm even as top government officials like Yellen warned the United States might end up defaulting on its debt. There were occasional tremors in equity markets and some dislocations in the pricing of short-dated Treasury securities, but overall financial markets took the threat of default in stride. After all, it was always an extremely unlikely event, and similar threats in 2011 also came to nothing.

- To me this flags a risk of escalation. A deteriorating fiscal picture will make political disagreements on spending and taxes even more strident, and the temptation to resort to more extreme brinkmanship will increase, especially if the expectation is that financial markets will stay on an even keel.

The risk therefore is that default threats will become a more common negotiating tactic. Whenever we have a split Congress, the temptation to resort to the “nuclear threat” of blocking a necessary raising of the debt ceiling will be strong, and if financial markets again take it in stride, politicians might be tempted to push each other closer and closer to the brink. At the very least, this might give us further instances of government shutdowns; but we’ve survived similar episodes before. The global image of the United States and of the dollar will suffer, but for the foreseeable future I do not see a viable alternative to the dollar as the primary reserve currency, so here as well the impact might be limited.

The more political parties engage in brinkmanship over the level of debt without addressing the underlying fiscal weakness; however, the greater the risk that at some point this will trigger an unexpectedly sharp bout of market volatility.

The immediate crisis has been averted, but the shadow that rising debt casts on financial markets has gotten more threatening, in my opinion.

WHAT ARE THE RISKS?

All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal. The value of investments can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Bond prices generally move in the opposite direction of interest rates. Thus, as prices of bonds in an investment portfolio adjust to a rise in interest rates, the portfolio’s value may decline. Changes in the credit rating of a bond, or in the credit rating or financial strength of a bond’s issuer, insurer or guarantor, may affect the bond’s value.

IMPORTANT LEGAL INFORMATION

This material is intended to be of general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice. This material may not be reproduced, distributed or published without prior written permission from Franklin Templeton.

The views expressed are those of the investment manager and the comments, opinions and analyses are rendered as at publication date and may change without notice. The underlying assumptions and these views are subject to change based on market and other conditions and may differ from other portfolio managers or of the firm as a whole. The information provided in this material is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region or market. There is no assurance that any prediction, projection or forecast on the economy, stock market, bond market or the economic trends of the markets will be realized. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount that you invested. Past performance is not necessarily indicative nor a guarantee of future performance. All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal.

Any research and analysis contained in this material has been procured by Franklin Templeton for its own purposes and may be acted upon in that connection and, as such, is provided to you incidentally. Data from third party sources may have been used in the preparation of this material and Franklin Templeton (“FT”) has not independently verified, validated or audited such data. Although information has been obtained from sources that Franklin Templeton believes to be reliable, no guarantee can be given as to its accuracy and such information may be incomplete or condensed and may be subject to change at any time without notice. The mention of any individual securities should neither constitute nor be construed as a recommendation to purchase, hold or sell any securities, and the information provided regarding such individual securities (if any) is not a sufficient basis upon which to make an investment decision. FT accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss arising from use of this information and reliance upon the comments, opinions and analyses in the material is at the sole discretion of the user.

Products, services and information may not be available in all jurisdictions and are offered outside the U.S. by other FT affiliates and/or their distributors as local laws and regulation permits. Please consult your own financial professional or Franklin Templeton institutional contact for further information on availability of products and services in your jurisdiction.

Issued in the U.S. by Franklin Distributors, LLC, One Franklin Parkway, San Mateo, California 94403-1906, (800) DIAL BEN/342-5236, franklintempleton.com – Franklin Distributors, LLC, member FINRA/SIPC, is the principal distributor of Franklin Templeton U.S. registered products, which are not FDIC insured; may lose value; and are not bank guaranteed and are available only in jurisdictions where an offer or solicitation of such products is permitted under applicable laws and regulation.

_________

1. Debt held by public excludes debt held by federal trust funds and other government accounts, for example Social Security.

2. Source: CBO, “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2023 to 2033,” February 2023. There is no assurance any estimate, forecast or projection will be realized.