The Federal Reserve (Fed) kept interest rates on hold in its September meeting, but went out of its way to signal that the neutral interest rate is likely higher than the central bank has indicated so far, and that policy will have to remain tighter for longer—as I have long maintained.

The Fed’s new “Summary of Economic Projections” unveiled important changes to the Fed’s views and forecasts compared to June. On the macroeconomic outlook, the Fed now envisions a much stronger economy this year and next, with faster growth and lower unemployment. Gross domestic product (GDP) growth has been revised upwards by over one percentage point for this year, to 2.1%, and by almost half a percentage point for 2024, to 1.5%. The Fed now sees unemployment at just 3.8% by the end of this year, and only 4.1% in 2024 and 2025 – this compares to an already quite low path of 4.1%, 4.5% and 4.5% in the previous projections. The inflation path, however, has been left virtually unchanged, with core personal consumption expenditures (PCE) a tad lower this year at 3.7% (from 3.9%), unchanged at 2.5% for next year and close to target by 2025.1

Some analysts have been quick to criticize these forecast changes as inconsistent wishful thinking—projecting a stronger economy and labor market while maintaining the same disinflation path is overly optimistic, they argue.

I think the revised macro outlook makes sense once you put it together with the new monetary policy forecasts and signals.

I have been arguing for some time that the natural real rate of interest (the one that would be consistent with target inflation and full employment) is higher than that implied by the 2.5% long-term nominal rate in the Fed’s forecast. A higher natural rate would be consistent with the stronger growth we’ve been observing, and now acknowledged in the new Fed forecast. Indeed, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell conceded that the reason why the US economy remains so strong might well be that the natural rate is higher—in other words, that current monetary policy is not actually that restrictive. (I would add that extremely loose and loosening fiscal policy also contributes, as I argue below.)

Powell emphasized that the natural rate is hard to pin down, and stressed that whether policy is restrictive, “we’ll know it when we see it.” We’re definitely not seeing it yet.

Indeed, some Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) members are now pointing to a higher natural rate—the upper end of the forecast range for the long-run fed funds rate has risen to 3.3% from a previous 2.8%. I have argued in a previous “On My Mind” that the natural rate could be even higher, somewhere above 4% (back in 2012 the FOMC itself put it in a 4.0%-4.5% range). More than once during the post-meeting press conference, Powell reiterated that the natural rate of interest might be higher—this is a very important shift in emphasis, and a shift toward greater realism, in my view.

FOMC members also left the door open to another rate hike before the end of this year (with a 5.6% terminal rate unchanged from June), and now see a half a percentage point higher fed funds rate for both 2024 and 2025, at 5.1% and 3.9% respectively. Quite a strong indication that policy will be tighter for longer.

The way I put it together is this: The Fed realizes and implicitly acknowledges that policy is not as tight as it should be—or at least, as Powell put it during the press conference, has not been tight for long enough. This is reflected in robust economic growth and a strong labor market. Inflation has come down but not enough, and with a strong economy and monetary policy that might not yet be sufficiently tight, the risk is that disinflation progress might stall.

To get inflation back to target will require further tightening. In the Fed’s scenario, this will be achieved by keeping the nominal policy rate high (one more hike this year and at most two cuts next year) so that declining inflation delivers a higher real interest rate.

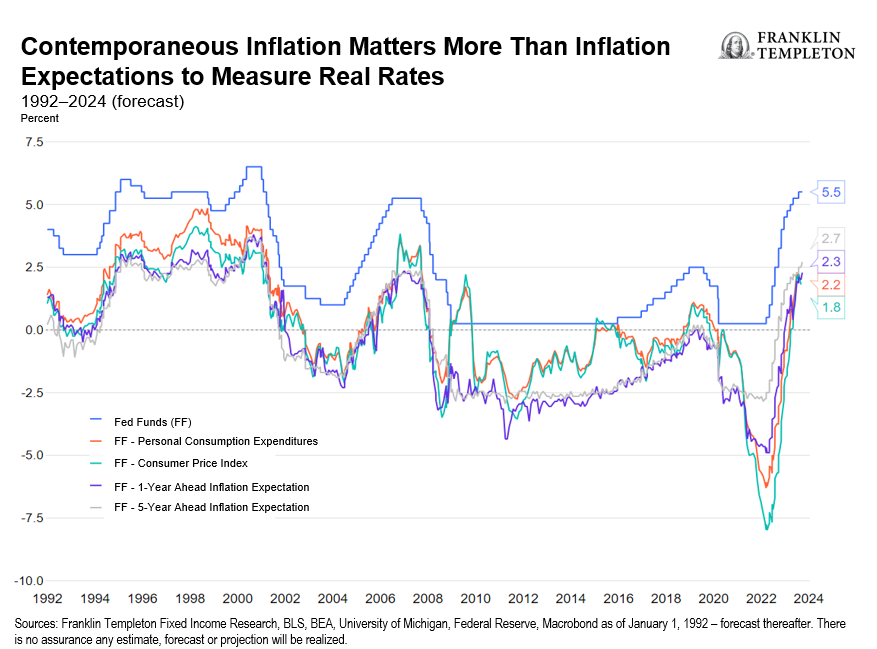

It is also worth noting that the Fed now acknowledges that contemporaneous inflation is what matters most to measure real rates, rather than future expected inflation. In the early phases of tightening, the Fed often argued that policy rates were already in restrictive territory when measured against inflation expectations—especially medium- or long-term expectations. I have always been of the view that contemporaneous inflation matters more, because that is what consumers and workers are feeling. As the chart below shows, measured against contemporaneous inflation (PCE or the Consumer Price Index), monetary policy has remained loose for much longer than measured against inflation expectations. The Fed’s focus now seems to have shifted more squarely to comparing policy rates with actual contemporaneous inflation.

Exhibit 1: Fed Funds Rate vs. Expected and Actual Inflation (right click to enlarge chart)

This combination of forecasts and policy signals is probably also the most effective and least disruptive way to guide market expectations toward a return to the old normal of higher rates (pre-global financial crisis).

What about the risks to the outlook? The press Q&A with Powell highlighted a number of downside risks, from labor strikes to the looming threat of a US government shutdown, to the resumption of student debt payments to a possible spike in energy prices. I would argue that a government shutdown might have at most a moderate temporary negative impact, and an energy price spike would also rekindle inflation and inflation expectations. And let’s not forget that the latest Congressional Budget Office forecasts point to a fiscal deficit of about 7% of GDP this year, which would represent a substantial fiscal loosening from last year’s 5.5% of GDP.

I have long been arguing that investors should prepare for a reversion to the “old normal” of higher rates—which was the long-term norm before the exceptionally loose policies that followed the global financial crisis and the pandemic. The Fed is now acknowledging that this is indeed the most likely outlook. The shaky fiscal outlook poses further upside risk to yields in the medium to long term. Financial markets have started to accept this, but in my view, the adjustment process will take longer and bring more volatility.

WHAT ARE THE RISKS?

All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal.

Equity securities are subject to price fluctuation and possible loss of principal.

Fixed income securities involve interest rate, credit, inflation and reinvestment risks, and possible loss of principal. As interest rates rise, the value of fixed income securities falls. Low-rated, high-yield bonds are subject to greater price volatility, illiquidity and possibility of default.

IMPORTANT LEGAL INFORMATION

This material is intended to be of general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice. This material may not be reproduced, distributed or published without prior written permission from Franklin Templeton.

The views expressed are those of the investment manager and the comments, opinions and analyses are rendered as at publication date and may change without notice. The underlying assumptions and these views are subject to change based on market and other conditions and may differ from other portfolio managers or of the firm as a whole. The information provided in this material is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region or market. There is no assurance that any prediction, projection or forecast on the economy, stock market, bond market or the economic trends of the markets will be realized. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount that you invested. Past performance is not necessarily indicative nor a guarantee of future performance. All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal.

Any research and analysis contained in this material has been procured by Franklin Templeton for its own purposes and may be acted upon in that connection and, as such, is provided to you incidentally. Data from third party sources may have been used in the preparation of this material and Franklin Templeton (“FT”) has not independently verified, validated or audited such data. Although information has been obtained from sources that Franklin Templeton believes to be reliable, no guarantee can be given as to its accuracy and such information may be incomplete or condensed and may be subject to change at any time without notice. The mention of any individual securities should neither constitute nor be construed as a recommendation to purchase, hold or sell any securities, and the information provided regarding such individual securities (if any) is not a sufficient basis upon which to make an investment decision. FT accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss arising from use of this information and reliance upon the comments, opinions and analyses in the material is at the sole discretion of the user.

Issued in the U.S. by Franklin Distributors, LLC, One Franklin Parkway, San Mateo, California 94403-1906, (800) DIAL BEN/342-5236, franklintempleton.com – Franklin Distributors, LLC, member FINRA/SIPC, is the principal distributor of Franklin Templeton U.S. registered products, which are not FDIC insured; may lose value; and are not bank guaranteed and are available only in jurisdictions where an offer or solicitation of such products is permitted under applicable laws and regulation.

Products, services and information may not be available in all jurisdictions and are offered outside the U.S. by other FT affiliates and/or their distributors as local laws and regulation permits. Please consult your own financial professional or Franklin Templeton institutional contact for further information on availability of products and services in your jurisdiction.

________

1. There is no assurance that any estimate, forecast or projection will be realized.